|

|

|

YOU ARE HERE:>>Collectors' Resources>>Essentials>>Researching your pieces page 7

AG: What are the particular characteristics of Chandraketugarh terracottas -- technical, artistic, or material-wise? If you see a piece of terracotta how would you determine if it's from Chandraketugarh?

JKB: It's not so easy to answer this in such a short span. What separates Chandraketugarh terracottas is not some rendering styles, such as the eye having double outline, or nose is done in a particular way. In fact, I cannot easily describe to you these characteristics. But if you work for a period of times with these terracotta objects, you simply "know" where a given object comes from, without rationally knowing why. Because the production is so rich -- there are plaques - hand modeled, half hand-modeled, matrix modeled, mixed processed, softer burns, burned with less Oxygen etc., -- . It's difficult to make a general statement. Also no art offers more exceptions than Indian Art.

If you consider a narrow category such as the hollow terracotta pieces (also called rattles, tricycles and toy carts), I can easily tell the difference if you give me two pieces. But to describe it theoretically is different.

AG: So there aren't any describable difference in terracotta from these centers?

JKB: There is a clear stylistic difference. But first, you need to compare something to some other thing. You have to start your comparison from a fixed point, and if you don't establish this point you can't do any comparison. For terracottas it is not clear what should be this standard fixed point.

AG: How about differences based on the depicted contents?

JKB: Not much, since the content is all Indian. For example consider the story of the Jataka about a monkey crossing the river on the back of a crocodile. Depictions of this story have appeared in several Chandraketugarh and other terracottas in India. But the story is well-known all over India, and from this point, the terracottas can be from any part of India. Some plaques are difficult to determine geographically. But show me two terracotta pieces, and I'll tell you why one is from one place and the other is from a different place.

No general statement is possible to make, because the examples are different. So I will be cautious to say something like "Chandraketugarh terracotta are easily recognizable due to these features...".

AG: In your book you say "A useful frame for a more precise dating is provided by the excavation report on Sonkh near Mathura. The majority of the terracottas reproduced here (by here Bautze means the BOOK) , however, stems from the areas around Kaushambi and Chandraketugarh " - please explain.

JKB: The publisher didn't want to reproduce fragments but complete terracotta. There are reliable stratographical excavation reports e.g., in Sonkh (by my Ph.D. advisor) -- so the periods are datable. Not much was done in Kaushambi and Mathura which are reliable -- I wish there will be more. Nothing much is available. Complete pieces come from private collections, so unauthorized, clandestine and unofficial sources.

Prof. B. N. Mukherjee published a photo in one of his recent Bengali booklets not knowing that the photo was originally published in my book.

AG: Is it possible for an experienced researcher to do a synthetic work on the history, economy, society and culture of Chandraketugarh from the available art materials, inscriptions and the geographical data? I am thinking of a description of the people - their day to day lifestyles, beliefs, food habits etc.

JKB: In absence of more historical material it's hard... what is lacking in any period of Indian art is a newspaper or journalistic reporting such as the inauguration of a king or the visit of a dignitary, and information of this type. All we have are the art objects and a few inscriptions, other than the Stupas and Toranas. Books on social life have been written on some historical sites (such as Sanchi) but these are all based on conjectures, and therefore are not very scientific.

Indians were never great historians. What we know about the Buddhist and the early Buddhist periods are practically exclusively from Chinese descriptions. They supplied all the information. The importance of Nalanda and Bodhgaya are testified through Chinese or Burmese sources and not through genuine Indian sources. So the topic you suggest will be interesting but it will lead to nothing that will convince me.

Why don't we take the art objects as they are? Why do we always try to... it's like you find the skeleton of a dinosaur and trying to reconstruct how it looked like, what it ate, how it mated, how many eggs it hatched etc. It's not the job of an art historian to do that. It is somebody else's job. But that somebody else first needs to undergo training in art history in order to distinguish between all the deities and gods etc. and then..

During excavations we have found glass beads necklaces... gold jewelry, granulated gold -- they tell us that people had very good taste but not much about their social status. The pieces put them in the map of world art. Why do we need to do more? Everybody should be happy with that.

After having lived in the rural lower Bengal villages without the amenities, I would say that life probably didn't differ that much in those rural areas 2000 years ago.

AG:...Is this opinion confirmed by what you notice on the terracottas?

JKB: No, it's more wishful thinking.

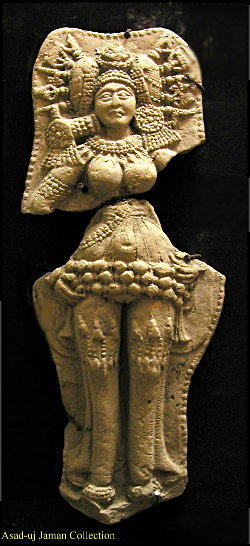

AG: For example, women these days are not seen wearing the gigantic headdresses with 10 hairpins routinely seen depicted in Chandraketugarh.

JKB: Japanese women used to do it until recently. Until the Sunga or Kushana period both men and women used to have huge headgears to maintain a huge quantity of hair. But that doesn't allow us to draw any conclusion.

AG:... Are the plaques then depictions of totally fictional people or the realistic depictions of a certain class of people?

JKB: Can't tell. Look at the prodigious amount of granulated gold in the Tamralipta plaque in Oxford,

http://www.ashmolean.org/ash/objectofmonth/2004-04/theobject.htm

This terracotta plaque, commonly called the Oxford Plaque, is one of the finest examples of early Indian terracottas to survive. It was discovered in ancient Tamralipta, present day Tamluk in India, and it dates to around the first century BC. The iconography of the figurine has fascinated and intrigued scholars for over a century, and research continues in order that we might find out more about this exquisite figurine.

The figurine has been made from terracotta using a clay mould. Extra details such as the rosettes in the background would have been added on by hand.

The costume and large turban she is wearing are very elaborate. Look closely and you can see five different shapes on the left side of her headdress. Scholars think that these perhaps represent weapons.

The fine incised lines on her torso and her legs indicate that she is wearing a garment of some sort, together with a sash that she has draped over her arms. This type of costume is quite unusual for figurines of the time as usually their upper bodies are left bare. She is also wearing a large quantity of very elaborate jewellery and she is covered with strings of pearls, beads and ribbons. If you look closely you can see that she has four human figures attached to her belt. These are thought to be yakshas or ancient nature spirits.

-- she wasn't the wife of a poor peasant with 1 sq. m of paddy field, but the idealized depiction of a wealthy person. Excavation has brought up many similar objects, but whether they were actually used by the majority or the minority of people, you just can't tell.

For example, if you go by the Ajanta paintings, you would think that dark complexion was the ideal of beauty. Today it is the other way around and people want to have fair complexion rather than dark complexion.

AG: What are the European museums where one can find Chandraketugarh terracottas on display?

JKB: Musee Guimet, Paris, France

Linden Museum, Stuttgart, Germany

Museum of Indian Art, Berlin, Germany

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK

probably also the Victoria and Albert and the British Museum, London

I know collections even in Japan. Not in museums yet.

Chandraketugarh terracottas were not available 50 or 100 years ago. Even 15 years or so ago, the dealers used to freely give a few terracotta pieces accompanying a stone statue to the purchasing museums. This is how several of the museums obtained those pieces.

AG: I wanted to put pictures of Chandraketugarh teracottas from private collections on this website. I was told by researchers and museums that the private collectors wouldn't want that and they don't want their names to be known because of legal issues.

JKB: Not true. The private collectors would love their collection to be known. Scholars don't want to give access to their "stock" of collectors to other scholars. Perhaps this is a form of professional greed.

Collection links.

http://www.historyofbengal.com/dilip_maite.html

http://www.historyofbengal.com/asad_uj_jaman.html

What about FAKES of this type of terracotta?

![]() For information about fake terracottas of this type see here>>>

For information about fake terracottas of this type see here>>>

Home | About This Site | Privacy Statement | Gallery | Testimonials | Guarantees

About Collectors' Resources pages | What's New

Search | Site Map | Contact Us